Some images stay with us for decades, resurfacing to link places and times that once seemed far apart. Three works of mine—from 1994, 2016, and the present—trace a continuous thread through themes of deindustrialization, anonymity, and urban life.

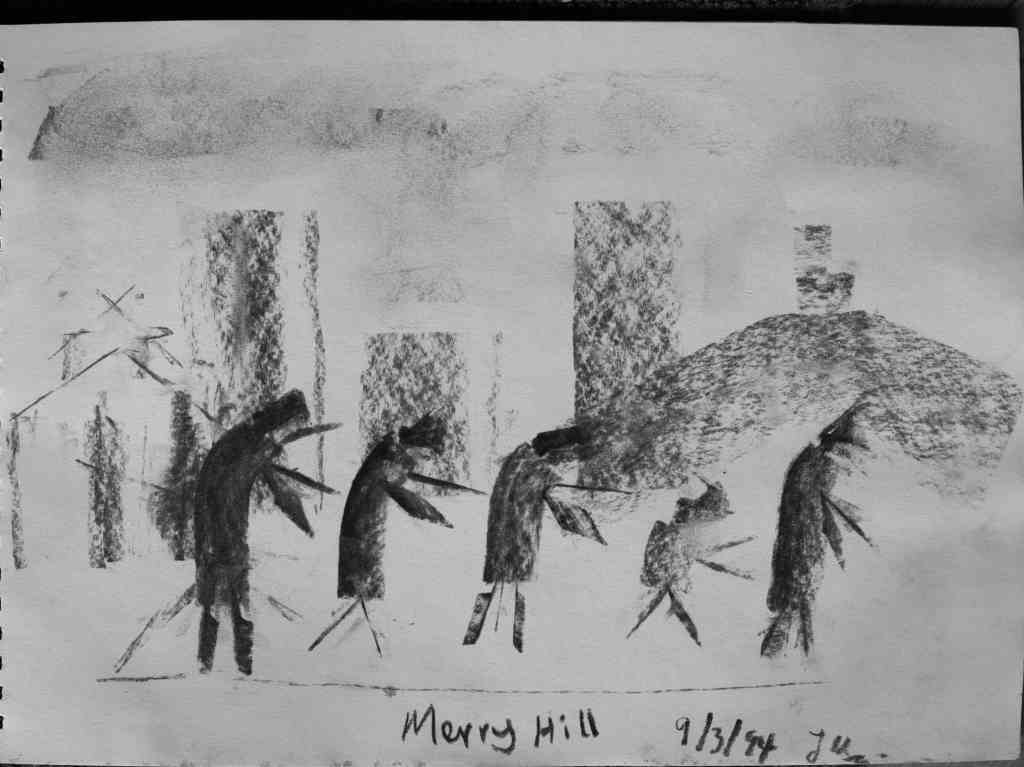

Dudley, 1994

I stayed in a hotel inside the newly built Merry Hill Mall. It did not feel merry. It echoed the steelworks and housing that had been cleared away. This drawing, made rapidly in charcoal, captures a landscape where industry had given way to retail, yet without comfort. The figures bend forward, anonymous, trudging through a place drained of joy.

For over twenty years this picture was lost, only resurfacing recently. Seeing it again, I was struck by its closeness to the Chicago work, despite being created in isolation. Its rediscovery started me thinking about the connections between them.

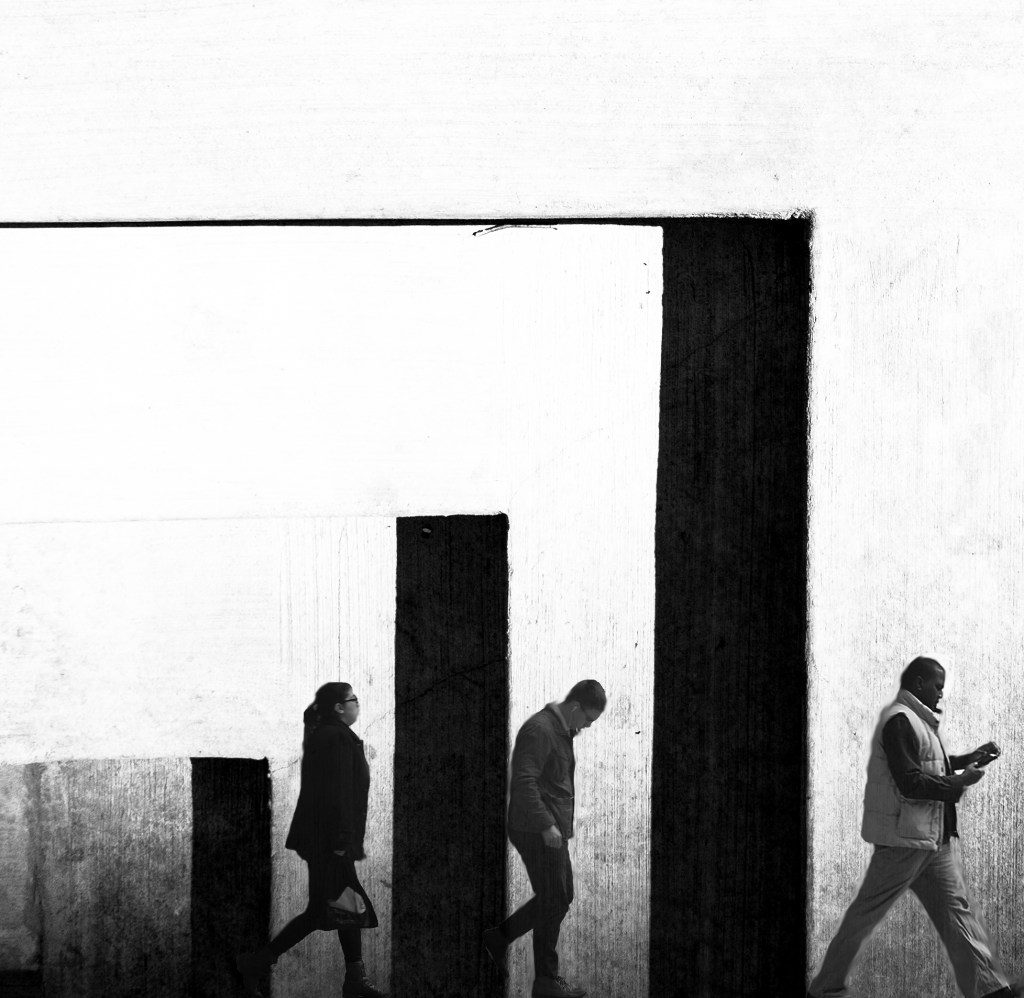

Chicago, 2016

More than twenty years later, in Chicago, I made a second image. I was struck by the sight of people bent under routine, and thought of Lowry’s figures moving through harsh geometries. People pass in isolation, dwarfed by blocks of black and white. This picture echoes the first: a different continent, but the same themes of anonymity, repetition, and endurance.

Permanent Storage

The third piece, from 2016, was part of a series I titled Travellers. It imagines shadows left behind, as if seared onto concrete. It hints at rupture and at cracks where glimpses of something else might be caught. Unlike the first two, which show figures locked in a cycle, this one suggests the possibility of movement between states—a faint hope of passage.

Methods and Media

The first work is charcoal on paper, capturing immediacy and atmosphere. The later two are manually constructed collages of photographs, layering fragments of reality into new forms.

Shared Themes

- Deindustrialization and its aftermath.

- Figures reduced to silhouettes, caught in systems larger than themselves.

- Urban environments that absorb individuality.

- A longing to break free, even when unsure where freedom would lead.

Motivation and Context

The Travellers series, which includes Permanent Storage, began with a collaborative and technical process. I was working with other artists to create double-exposure films, combining images from separate locations. During this time, I was reading John Berger’s essay “Understanding a Photograph,” which argues that a photograph represents a specific moment selected by the photographer, removed from its original context in time.

My goal became to challenge that singularity of context and moment. I set out to create digital collages from elements shot over an extended period in various places, making new wholes from choices made across time. I explored how isolated each element felt—whether people looked out of place or belonged.

Permanent Storage is a result of that process. While other pieces in the series play with whimsy or dislocation, this one represents something impossible and more profound: people merging into an inanimate object. It connects directly to my concerns about nuclear weapons, where a flash etches the shadows of people onto concrete. In this way, the series moves from technique to philosophy: these constructed images become like Berger’s “traces of lived experience,” not as single moments, but as layered fragments of memory and history. They are not polished answers but hints at what lies behind the visible.

Closing Thoughts

These works span decades, yet they circle the same ideas. Have the places shaped the pictures, or has my own perspective repeated itself across time? The third image may be the outlier, or it may point to a shift: a suggestion that through cracks in the wall, something else can be seen.

Clear lines, simple forms, recurring shadows—together they form a record of how environments shape us, and how, even in repetition, the possibility of change remains. Perhaps the shadow is not only a mark of what has been lost, but also a doorway to what is still possible. The rediscovery of the first picture, long missing, underlines this: what is forgotten can return, linking distant times and places.